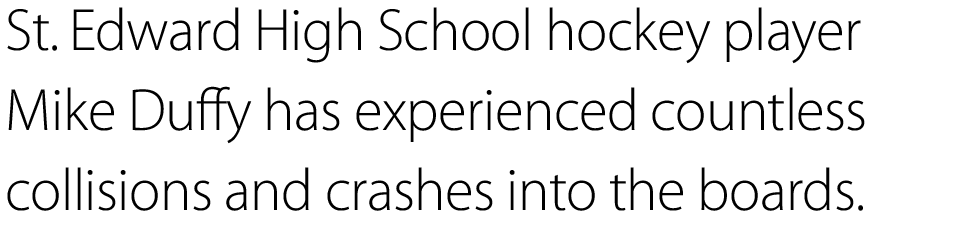

Football accounts for the highest number of concussions in high school sports. But concussions affect athletes across every sport — even those not considered “full contact.”

But nothing like the illegal check that rocked him this season. Although he managed to finish the game, his head throbbed and he was falling asleep in class. He didn’t know it at the time, but he had a concussion. A bad one.

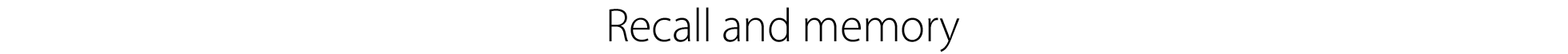

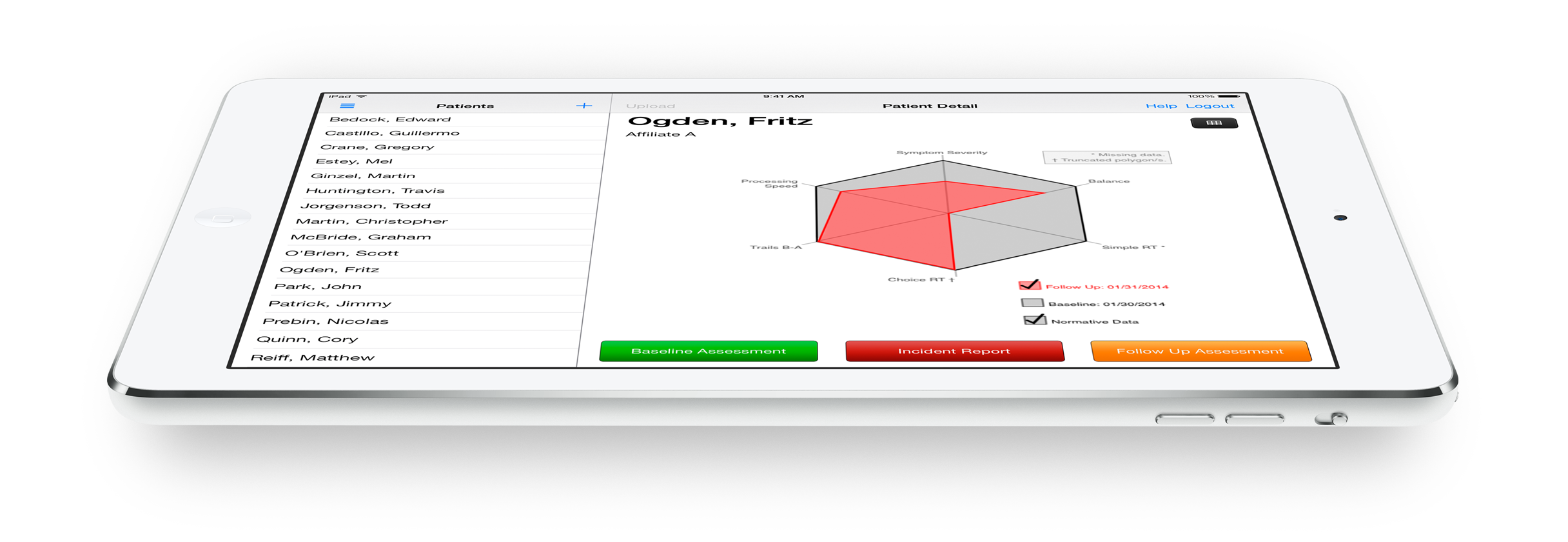

According to athletic trainer Jason Cruickshank, Duffy was lucky his concussion was caught. His team is part of a program that uses iPad with the C3 Logix app to measure and monitor concussion symptoms among all student athletes. “There are obvious and not-so-obvious concussions,” he says. Playing with one puts an athlete at risk for much worse injury. And young athletes are even more vulnerable because their brains are still developing.

In the past, it was easy to miss a concussion because of highly subjective reporting from athletes and errors made during paper-and-pencil data collection. But with iPad and the app, Cruickshank can make injury assessments based on precise measurements. “Using iPad with C3 Logix, we get hard, factual data that we can put in front of the athlete and say, ‘Look, this is where you should be.’”

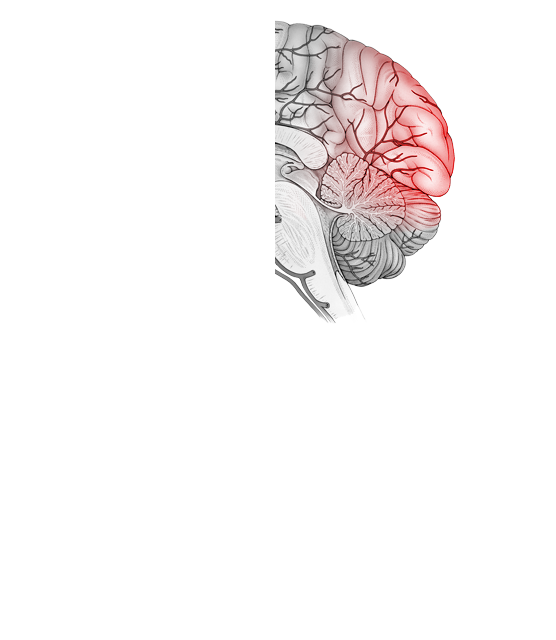

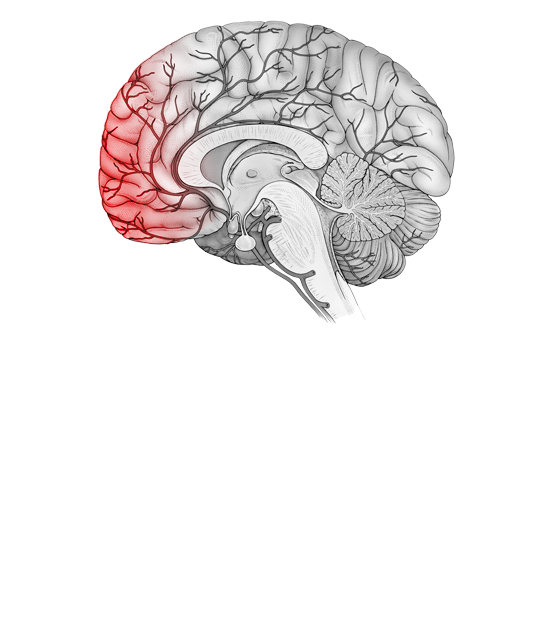

A sudden impact to the head causes the brain to slam against the inside of the skull, creating a coup injury. The brain can then rebound and strike the skull on the opposite side, causing a contrecoup concussion.

Even before the season is under way, Cruickshank gets a jump on managing potential injuries. It begins with using iPad and the app to take baseline measurements of athletes in normal states. When a possible concussion occurs during a practice or game, he examines the athlete and then takes him to the locker room for a postinjury retest. By comparing those results with the baseline, Cruickshank can easily spot a drop in performance that might indicate concussion.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A concussion isn’t like a broken arm. It doesn’t show up in an X-ray or even an MRI. So to accurately monitor the injury, you need to visualize its effect on a person’s cognitive and motor performance. The C3 Logix app uses a hexagon-shaped graph to represent the multiple symptoms associated with concussion. The athlete's normal level of function is shown on the perimeter, with postinjury results inside. During recovery, the inner graph moves out toward the perimeter.

There is no typical recovery from concussion. And it’s not always clear when a full recovery has occurred. So as injured athletes progress, trainers like Cruickshank are with them every step of the way, monitoring their performance with C3 Logix on iPad. Typically, he tests them every five to six days. Because all the data collected on iPad is stored by the app, Cruickshank can share a complete picture of the athletes’ progress with doctors, parents, and coaches. That makes it much easier to judge when it’s safe for an athlete to return to action. St. Edward hockey coach Troy Gray says that seeing the persuasive test data is making his athletes more likely to cooperate with treatment and requested breaks from play.

Given the significance of his injury, Mike Duffy’s return to school and hockey was surprisingly smooth. After a month of rest, rehab, and weekly testing, he was cleared to return to finish the season. “iPad let me judge my own progress,” he says. “I’m feeling fine now, and I’m back to my game. This recovery is 100 percent.”